Annette, our daughters and I spent New Year’s Eve in Bonn with Annette’s two sisters and their families. On the drive back to Berlin, I heard numerous reports on the radio about an explosion in the Nordrhein-Westfalen town of Euskirchen. The operator of a large excavator working at a rubble disposal yard had been killed when his machine struck what was thought to be unexploded ordinance from WWII. Windows within a 500 meter radius were shattered by the blast. Debris from the explosion was found nearly a kilometer away. The authorities believe that this bomb may previously have been encased in concrete, as was sometimes done when defusing was not feasible.

Approximately one tenth of the millions of bombs dropped by British and American planes on Germany during WWII did not explode. Every year, over 2,000 tons of unexploded bombs and other munitions are recovered. Unexploded ordinance is common enough that companies routinely hire private bomb disposal teams to check that sites are safe prior to construction. Safely disposing of the bombs is increasingly difficult as they decay over time.

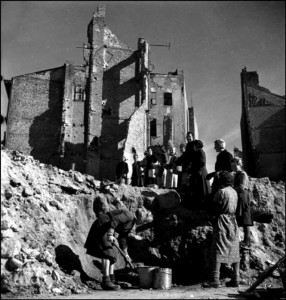

Berlin and the surrounding area is one of the most munitions-contaminated areas of Europe — a legacy of heavy Allied bombing right up until the end of the war. Photos of post-war Berlin tell part of the story:

Berlin in 1945 was a city filled with rubble:

The brigades of women who helped to clear the debris were known as Trümmerfrauen, or Rubble Women:

While the central areas of the city were devastated, some of the outlying neighborhoods were spared heavy damage:

As I travel around Berlin, I can’t help but notice the contrast of pre-war buildings adjacent to those constructed after the war. The city abounds with these juxtapositions:

These two examples are within a block of our apartment:

Many of Berlin’s utilitarian-looking apartment buildings were actually originally built before the war. Following the war, buildings that were not too heavily damaged to salvage were rebuilt quickly and simply, to address the acute housing shortage. Ceiling heights generally indicate whether buildings are pre- or post-war. Post-war buildings fit five floors into the height occupied by four in an Altbau. An unadorned building may have high ceilings and Altbau bones.

This is one of my favorite juxtapositions. The older building seems to be leaning on the new:

Here’s a subtle example not far from our apartment:

The building was originally built symmetrically, with four window openings on each side of the entrance, and a hipped roof at each end. The right end was presumably damaged during the war, and subsequently lopped off like an amputated limb.

Where did all the rubble from the demolished buildings end up? Much of it became the Teufelsberg, or Devil’s Mountain. After a recent visit to my brother-in-law Stefan’s dental office on the fifth floor of a building downtown, I looked out the hallway window and saw a small rise on the horizon. I realized that it was the Teufelsberg, located in the Grunewald park:

Under the Teufelsberg are the remains of a Nazi military-technical college that was designed by Albert Speer, but never completed. Following the war, the Allies attempted to demolish the school with explosives, but it was so heavily built that covering it with debris was deemed to be easier.

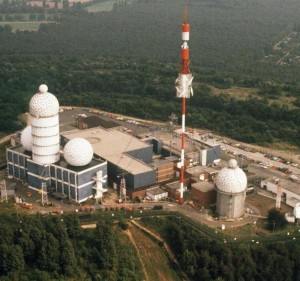

During the Cold War, the NSA built a sophisticated listening post on top of the Teufelsberg, for eavesdropping on communications behind the Iron Curtain:

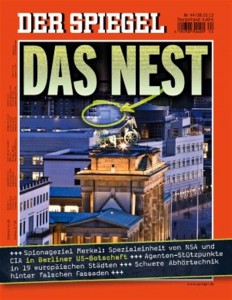

These days, the listening post atop the Teufelsberg is a neglected ruin, and the NSA is apparently eavesdropping from more central locations like the US Embassy in Pariser Platz:

Yesterday Annette and I went mountain biking on the wild boar-rutted trails around the Teufelsberg:

When I saw this chunk of masonry debris lying in the still forest, I wondered what stories it had to tell:

Hey there! I love the blog. Peggy