In a recent New York Times article about the changing face of Brooklyn, A.O. Scott writes “Every city is simultaneously a seedbed of novelty and a hothouse of nostalgia, and modern New York presents a daily dialectic of progress and loss.”

The same could be said of Berlin.

Some weeks ago I came across a building called Tacheles that I had not seen in fifteen years. It was more like the shell of a building, although that was already an apt description when I first saw it in January of 1998. Back then I was visiting Germany — and Annette — for the first time. Since Annette was working during the day, I spent much of that visit biking around the city and looking at buildings.

Berlin was rougher back then, more of a work in progress. Numerous tower cranes punctuated the skyline like so many erector sets. Postdamer Platz was a huge hole in the ground. The latest proposal for the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe was being hotly critiqued. And although the Berlin Wall had been down for nearly ten years, the differences between East and West Berlin were still evident. The majority of the drab GDR-era buildings in East Berlin had not yet been renovated (the German word is saniert, which has the same Latin root as “sanitized”). I marveled at the pockmarked stone exteriors of many buildings in the East. The East German government apparently had more pressing concerns than patching holes left by bullets and shrapnel from World War II.

One evening during that first visit to Berlin, Annette took me to Tacheles. If she was trying to impress me, it worked. Before World War II, Tacheles had been a department store in the city’s Jewish quarter. The building was damaged during the war, and never repaired. Portions of the structure were demolished in 1980, and the rest was scheduled to be taken down in 1990, but a group of artists staged a protest that eventually led to the building being granted historic landmark status. When Annette and I were there in 1998, Tacheles was a graffiti-tagged warren that included artists’ ateliers, funky places to eat and drink, and a small movie theater. Music and smoke hung in the air. Because sections of the rear wall of the building were missing, one could see into some of the rooms from the sculpture garden behind the building. The menu at the restaurant where we ate was printed on an Eviction Notice for the building’s occupants.

Seeing Tacheles recently brought back memories of what Berlin was like in 1998, of who I was — a young man falling in love — and of who Annette and I were — a couple embarking on a shared life. Berlin has changed, as have we.

Although construction is still thriving in Berlin, one no longer senses that a city is being remade. As I bike through the city these days, I cannot distinguish what was West from what was East. One has to look closely to find evidence of the Berlin Wall. The no-man’s land through which the wall ran, and in which over one hundred people were killed, is difficult to trace. At Checkpoint Charlie, which was one of the primary passage points through the wall, tourists have their photos taken with entrepreneurs dressed like Soviet soldiers.

It used to be that one could tell East from West by the style of the traffic lights for pedestrians, which were distinctive in the segregated city. In GDR-controlled East Berlin, the “Ampelmann” was a cartoonish character in a dapper flat-topped hat who — in his green incarnation — appeared to be striding briskly toward an important destination. In West Berlin, the crossing guard was more generic, something like a bloated stick figure.

During the past two decades while the cleansing cloth of capitalism burnished what had been East Berlin, the East German Ampelmann infiltrated West Berlin. Perhaps it would be more accurate to say that he was co-opted by his capitalist liberators. In the mid-nineties when the government of re-united Berlin began replacing the East German Ampelmann with the more generic West German version, a resistance movement arose. The “Committee for the Preservation of Ampelmen” was founded, and public support eventually reversed the decision to do away with that vestige of Communist life. The East German Ampelmann can now be found at intersections throughout the city. In fact, he has become such an icon of today’s Berlin that one can now buy Ampelmann mugs, key chains and t-shirts in numerous stores dedicated to his proliferation.

The East German Ampelmann may have survived, but as property values in Berlin have risen, alternative art venues, galleries and clubs have come under increasing pressure. The last of the artists squatting in Tacheles were cleared out by the city in 2012. Although the spirit of Tacheles is still alive in Berlin, it’s harder to find. Annette and I had a taste of that rough, creative energy a few months ago when we attended the show of our friend Caitlin Baucom, a performance artist.

Caitlin’s performance was at a venue called Naherholung Sternchen, which might be translated as “Little Star of Nearby Recreation.” It was hard to find, tucked away within a nondescript GDR-era housing project. When we arrived in the area on our bikes, we circled the block a few times, looking for a sign, worried that we were late. We noticed several other people on foot who appeared to be doing the same. Eventually we discovered that a dark doorway which looked locked actually opened into a bar.

It turned out we were among the first to arrive. The cover charge was by donation, and the woman who stamped our hands seemed surprised when I offered ten Euros each for Annette and me. I wondered whether I had just outed myself as a member of the bourgeosie.

The place was cold and disheveled. It looked as though it had been abandoned and then recolonized. Equipment was casually being set up around a small stage. We made our way over to the makeshift bar. Even though Annette doesn’t usually drink beer, it seemed like that kind of a place, so I ordered two. We debated buying a pack of cigarettes from the machine in the corner, but decided that wouldn’t be necessary due to the potential for second-hand smoke.

We tried to guess who in the bar was Caitlin, because we had never actually met her. I started to approach a woman lounging at the bar who fit my mental image of a performance artist, but when I heard her speaking fluent German, I figured she was not Caitlin — an American who is spending three months in Germany for an artist residency.

Eventually we did meet up with Caitlin, in one of those “might you be the person I’m looking for?” instances of prolonged eye contact. She described her artist residency to us, and we told her of our life in Berlin. Soon we were comparing notes about people and places we had in common from the picturesque New England village where she grew up and that we call home. Conjuring Walpole, New Hampshire in a dark, grungy Berlin bar felt odd to me, but we enjoyed discovering the common connections.

An hour or so after the show was scheduled to begin, the now-sizeable crowd was herded to an outside courtyard for the first performance. It featured a woman slowly and deliberately setting fire to a series of cardboard boxes, against a backdrop of projected images. She called it “live sculpture.” Mid-way through the performance the wind picked up. Anyone whose attention had wandered was brought back to the moment as wisps of burning cardboard swirled into the crowd.

The second performance was in one of several empty rooms adjacent to the bar. The room was slightly less cold than the courtyard. A woman slapped hunks of clay on the concrete floor, then formed it into balls and flung them against the walls. She was accompanied by a drummer who beat skilfully on various found objects, his rhythms looped and layered through a sound system.

Back in the bar, we found that someone had set up a primitive propane burner that was struggling valiantly to take the chill off one corner of the room. We hovered around the flame and waited for Caitlin to take the stage.

Although I haven’t seen enough performance art to be a competent judge, Caitlin’s performance seemed to be more thoughtful and compelling than the others. She combined video containing suggestive imagery with her own movement and singing. She has a beautiful voice that contrasted jarringly with her body language and the images she presented. Her performance held my attention, and elicited a range of emotions.

The final performance was billed as a “porno choir.” It consisted of two women sitting on a couch, panting and moaning to the soundtracks of pornographic movies from the 1970’s. I suppose it could have been interesting, but it wasn’t.

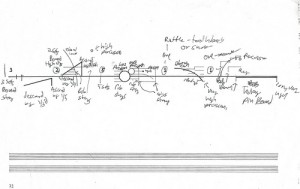

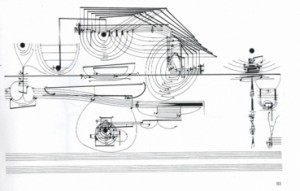

We stayed on to hear the first of several scheduled musical performances. An ensemble that included a viola, a stand-up base, a clarinet and drums performed a piece composed by Cornelius Cardew called “The Great Learning.” Apparently it’s based on translations of Confucius made by Ezra Pound. Because the composer intended for his score to be flexibly interpreted by the musicians, he wrote it using a combination of graphics, text and notations.

The musicians were accomplished and their performance did suggest spontaneity, but the late hour and the cold were diminishing my ability to appreciate avant-garde art. We made plans with Caitlin to get together the next day, and headed home across the city.

As Annette and I biked together through the chilly night, I was reminded of similar late-night return trips that she and I had made through a city that was fifteen years younger. Berlin is no longer the same, nor are we, but a certain essence endures.

Hello Andrew,

I so enjoyed reading this post-I loved it all – from reading about Tacheles and then bringing it around to Caitlin-very well done.

Looking forward to seeing all of you sometime this fall.

Lots of love,Paula