The Gasometer is one of several unusual structures that I have glimpsed repeatedly over the years while biking through Berlin.

Like the spherical water tower in Park Gleisdreieck, reminiscent of a WWI-era pickelhaube helmet,

and the giant pink pipe at the west end of the Tiergarten,

I have wondered about the Gasometer’s history, use, and future. Last Friday my questions were answered when Annette, her cousin Katrin and I climbed 420 steps to the top of the 80 meter tall structure.

We and the five other participants started the tour outside the cafe adjacent to the Gasometer. Our guides Jan and Jule stood before a table on which eight pairs of binoculars had been spread, and went over the guidelines for our ascent.

“You’ll probably each want to take up binoculars,” Jule said. “Please turn off your cell phones. Leave all knapsacks, purses and bags with me. I’ll be staying on the ground while you all go up with Jan. He and I will be in touch by radio. If anyone feels the need to turn back, that’s okay. I’ll even come up to meet you, if necessary. But for each level of the Gasometer that I have to go up,” she smiled, “you’re going to owe me a six pack of beer.”

Jan presented us with a bit of history. We learned that the word gas was coined in the mid-17th century by the Flemish chemist J.B. van Helmont, probably from the Greek word khaos, “empty space.” In the 18th century, a burgeoning interest in ballooning led to the development of processes for generating lighter-than-air (and flammable) gases from coal. By the early 1800’s, commercial gas works were providing lighting to many cities in England, and the technology was spreading to France and beyond. The artificial lighting made possible by gas facilitated profound changes on many fronts. Factories could operate at night, cities became safer, reading books at night was much easier, and theatrical lighting revolutionized dramatic performances.

Although electric lights have replaced gas lamps in most cities, most of Berlin’s streets are still lit with gas. With over 44,000 lamps in use, Berlin’s gas lighting network is the largest in the world. At the west end of the Tiergarten park, there is an open-air museum dedicated to gas street lamps, with about ninety working specimens on display. There’s even a verein — an official association — dedicated to the study and appreciation of Berlin’s gas street lighting.

Jan told us that the Gasometer was constructed in 1910 as a low-pressure container for natural gas. The original owner was a British company, the Imperial Continental Gas Association, which held a contract to provide gas lighting for the streets of Berlin. The Gasometer was located by a major railroad junction, to facilitate deliveries of coal to the adjacent foundry where the gas was produced.

“The industrial revolution was a messy business,” explained Jan. “Operations such as smelting iron and gasifying coal created lots of pollution. In Europe, the prevailing winds blow from west to east. You’ll notice that in most European cities, the historically working-class areas are toward the east.”

We started up the stairs. The steel stairway was rusty, but if felt solid.

We stopped at the first ring, where we had a close-up view of the structure, and of the bubble-like membrane roof of the space within the Gasometer.

The Gasometer contains a pressurized structure, like the temporary halls that are erected over tennis courts. Jan explained that the space inside is used for conferences and seminars, and that it also functions as a television studio for the German talk-show host Günter Jauch. He went on to describe the mechanics of the original Gasometer.

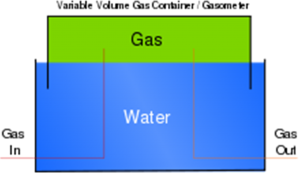

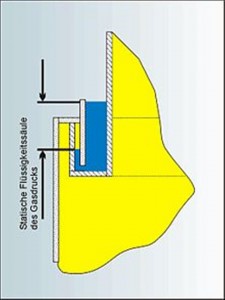

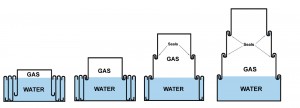

“You all know that air can be trapped under a cup if you place it upside down in water, right? Well, that’s the principle on which the Gasometer is based. The sides of the original Gasometer were made of telescoping rings, each sealed to the next with a trough of water. The rings were guided up and down along these beams.” He pointed to vertical I-beams. “The top of the Gasometer was a shallow bell that rose up and down depending on the volume of gas within.”

We continued climbing, up to the fourth ring. The city was starting to spread out before us. Jan pointed to the building adjacent to the Gasometer: “That brick building — the cafe — was the original foundry where coal was gasified.”

Jan told us that the foundry and the rest of the buildings in the immediate vicinity — many with solar arrays on top, and several sporting vertical-axis wind turbines — are part of a future-oriented technology park known as the EUREF campus. The project is the brain-child of Berlin architect and real estate developer Reinhard Müller. The goal is to create a CO2-neutral city district dedicated to innovation. According to EUREF’s website, “the vision of an ‘intelligent city’ of tomorrow is being developed at the EUREF campus today.”

The EUREF campus is still being developed, but already it is home to a branch of Berlin’s technical university (the “TU”), to established corporations such as Schneider Electric and GASAG, and to many clean tech firms. Electricity is provided to the campus by a combined heat and power (CHP) plant that is fueled with sustainably-produced biogas. Heat from the CHP plant flows to buildings and equipment through a network of insulated underground pipes. The heat is also used for cooling via an absorption chiller. Electricity from the CHP plant is distributed via a micro-smart-grid that allows for intelligent load management. All new buildings are being constructed to meet the LEED Gold standard. The campus is scheduled to be fully built out by 2018, at which point it is projected to be providing about 5,000 jobs. The total investment volume will be in the neighborhood of €600 million.

One hundred years ago, this historic site was central to the proliferation of a new energy technology that brought light to the streets and buildings of Berlin. Today on this spot, new energy technologies are being developed and tested that may once again revolutionize the production, delivery and use of energy in the city.

With that thought spinning in my head, I followed the rest of the group up to the top of the Gasometer. It was starting to feel very high. On the last set of stairs, someone ahead of me called out “Be careful here — this step’s loose!” After a moment of shocked silence, we all laughed nervously at the joke.

The wind was blowing hard up top, and the temperature — as we had been warned — was about ten degrees colder than on the ground. The two wind turbines that had recently been installed atop the Gasometer spun wildly. Everyone but Jan seemed to be clutching the steel rails with both hands, and stepping very carefully on the narrow catwalk.

“Don’t worry about the sign there that says the maximum load is 150 kilograms,” Jan said casually. “That was a reference to the original roof of the Gasometer. Whenever there was a snowstorm, someone had to climb up here and shovel off the roof. And they didn’t have those comfortable stairs that we just climbed up. They had to use this ladder.” He pointed to a narrow ladder adjacent to one of the vertical I-beams. I tried to imagine climbing the steel rungs after a snowstorm.

For the next hour, Jan led us on a 360 degree tour of the city from above. He pointed out landmarks, told stories about the city’s history — “that’s the building where Marlene Dietrich was born”– and explained the forces that shaped the built environment we were seeing from above. The angst that gripped me when I first stepped onto the catwalk never quite dissipated, but I did relax enough to be able to enjoy the breathtaking views.

Having lived in Berlin for nearly a year now, I found that I was well oriented to the neighborhoods below. As my gaze travelled over the rooftops, I could picture in my mind’s eye — like Google’s “street view” — what different areas looked like on the ground. I realized that I have internalized the city. It has become a part of me, and in some very small way, I have become a part of it. As the sun set over Charlottenburg and the texture of the city darkened, I felt as though I was beginning to say good-bye — or rather auf wiedersehen, “see you again” — to Berlin.