Note: on 15Oct13, a version of this post was run as a guest blog at GreenBuildingAdvisor.com

Der Spiegel is a weekly German news magazine whose gravitas I might have placed somewhere between Newsweek and The Economist. However, a recent cover story about Germany’s “Energiewende” did not strike me as particularly impartial or objective.

Energiewende literally translates as “Energy Turn,” but it is more typically expressed as “Energy Transition,” “Energy Transformation,” or “Energy Revolution.” The term refers to the German government’s 40-year plan to restructure its energy systems to achieve specific energy-related and carbon-reduction goals.

These goals include:

-

Reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 40 percent by 2020, and by 80 percent by 2050 (as compared to 1990 levels)

-

Phasing out the use of nuclear power by 2022

-

Reducing primary energy consumption by 20 percent by 2020, and 50 percent by 2050 (compared to 2008 levels)

-

Expanding the use of electric vehicles: 1 million by 2020, and 5 million by 2030

-

Increasing the percentage of energy from renewable sources to 18 percent by 2020 and 60 percent by 2050

A serious attempt at achieving these goals will require increasing the energy efficiency of all market sectors (housing, transportation, industry, etc.), dramatically expanding the use of renewable energy, and shifting energy-related attitudes and behaviors to a new paradigm.

One of my motivations for spending a year in Germany was to learn more about the Energiewende — to dig more deeply into the program specifics, and to find out how it is working.

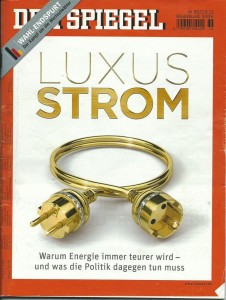

The cover of Der Spiegel caught my eye: “Luxury Power — Why energy will become increasingly costly, and what politicians must do to prevent it.” Aha, I thought, Germany has generally been the poster-child for the broad implementation of renewable power, and this article will provide insights into the downside of this transformation.

The cover of Der Spiegel caught my eye: “Luxury Power — Why energy will become increasingly costly, and what politicians must do to prevent it.” Aha, I thought, Germany has generally been the poster-child for the broad implementation of renewable power, and this article will provide insights into the downside of this transformation.

The article certainly does lambaste many aspects of the Energiewende, focusing particularly on the relatively high cost of electricity. But the sensational language employed and the apparent lack of context for some of the assertions had me wondering about the article’s credibility.

There’s no doubt that the German government’s subsidies for the development of renewable energy — particularly wind turbines and photovoltaic panels — have been expensive. These costs appear as a surcharge in the monthly electricity bills that most Germans pay. The article contends that this surcharge disproportionately penalizes low- and fixed-income citizens, many of whom are increasingly at risk of having their electricity cut off.

The German government’s energy regulations exempt businesses and industries that compete internationally from having to pay the electricity surcharge. This exemption represents a potential loophole that some businesses have exploited. It also increases the cost of power for those businesses that do not qualify.

The article contends that the main driver of increased electricity costs is the “haphazard” expansion of wind and solar energy. It describes the difficulties in bringing off-shore wind parks cost-effectively into operation, the need to upgrade the grid to transport energy from where it is produced to where it is needed, and the challenge posed by providing reliable back-up power during periods of peak demand.

The article points out the uncomfortable fact that Germany’s greenhouse gas emissions actually increased by 2% in 2012. This was presumably the result of the shut-down of eight aging nuclear power plants in 2011 following the Fukushima nuclear disaster, and the resultant need for Germany to use lignite coal-fired plants to pick up the slack.

The article concludes that Germany might be better off with a system based on market-driven incentives, similar to that which has been enacted in Sweden, rather than relying so heavily on government subsidies.

These critiques all have some merit, but reasonable arguments can be made in defense of the Energiewende’s policies and their implementation. Cogent responses to the concerns raised in this article can be found in the publication Energy Transition — the German Energiewende, produced by the Heinrich Boell Foundation. Chapter 6, Questions and Answers, addresses head-on many of the issues raised in the Der Spiegel article.

The Der Speigel article’s most significant omission, in my opinion, relates to efforts to reduce demand for energy. Energy efficiency is a cornerstone of the Energiewende, yet it is hardly mentioned in the article. Wind generators and solar panels lend themselves to simplistic critiques; insulating existing buildings and installing better building control systems are not attention-grabbing subjects. My understanding is that Germany is making steady progress in the arena of energy efficiency, but that there remains tremendous potential for additional gains.

What was most striking to me about the article in Der Spiegel is that it does not fundamentally question the need for an Energy Transformation; rather, it argues that the current path is flawed, and that alternatives should be explored. There seems to be general agreement within Germany that the Energiewende is a worthwhile endeavor, but one that should be subject to course corrections as it continues to unfold. Coming from the U.S., a country that lacks a comprehensive, coherent energy policy, I am inspired to see people here debating the “how,” rather than the “what” or the “why.”

Andrew,

Great blog! Looks like you guys are having a great experience. I look forward to future posts.

Best,

Ethan